The mighty James Malone tells deeply moving stories through film-making and stills photography. In the podcast discussion we recorded recently about his transition from life as a Royal Marine Commando to that of a creative professional, we talked about the grind that accompanies making authentic, important work. Spiritually it’s sometimes a struggle, financially it’s often a struggle, and emotionally it’s always a struggle. So it was not entirely a surprise when James recently posted about his love for a beautiful little short film about the sea, that just so happens to be my favourite short of all. I love the sea with a visceral passion and I miss it deeply when I’m away from it for too long.

Mickey Smith is a surfer, photographer, filmmaker and a musician. He’s a dyed in the wool son of Cornwall. When I heard him speak at the Do Lectures in 2011 his creativity and humility shook me to the core. He said something I’ve never forgotten:

“If I only scrape a living, at least it's a living worth scraping. If there’s no future in it, this is a present worth remembering.”

It’s the very same line that James referred to in his post.

Years later when David Hieatt asked me to write about a talk that had moved me for his Hiut Denim Yearbook, I wrote this:

The Lord of the Waves

Mickey Smith changed everything for me.

Mickey is a surfer, a photographer, and a musician. But more than that Mickey is a maker of visual and sonic landscapes, a student of nature and a philosopher.

When I responded to David and Clare’s invitation to support the Do Lectures mission back in 2008 I did so because of Mickey Smith. I hadn’t met him then, I’d never actually heard of him to be honest. But I had a hunch that the Do Lectures was all about the Mickey Smiths of the world.

You see Mickey Smith has a story that has to be shared. Not because he’s famous (although he certainly is in the cold-water surfing community), but because he’s an exceptional man.

Mickey grew up in West Cornwall, a place of outstanding wild and rugged natural beauty. A place he describes as being full of natural goodness, full of off-the-wall, crazy, lovely people. For anyone who’s visited, this is a place easy to rank as a jewel in the UK’s crown.

But West Cornwall has a darker side. It's a story of diminished and dying industries, a lack of opportunity, and of outsiders appropriating the best housing. A place Mickey has described as dead, with poor, unemployed ex-fishermen and miners fighting for scraps. It's a place where locals like Mickey can feel hopeless, like second class citizens, fish out of water, strangers in their own towns. And that was the story that was drummed into Mickey as he grew up. The story that West Cornwall had nothing to offer him.

But Mickey was a kid who always had a smile on his face. When a change in family circumstances promised upheaval, he spent a love filled summer on the beaches and in the sea off Land’s End, drifting on the waves. Shackled onto pieces of wood and plastic – floating in the ebb and flow on whatever he could find. Surrounded and nurtured by the love and shared laughter of his mum and sister.

And when Mickey started playing every musical instrument he could lay his curious hands on, and was later gigging weekly in pubs, clubs and festivals up and down Cornwall, his perception shifted. Life was not all doom and gloom. Driven by a desire to live creatively and to push the scope of his experiences, Mickey was able to start earning a living following his passions.

Living on the road, hand to mouth, sleeping on floors, in vans, and on beaches and in bushes, Mickey learned his trade. And his creative work started getting noticed.

Magazines wanted to publish his photography and the surfing fraternity wanted to commission his cinematography. Because Mickey’s work was a rare thing. It was made with soul. An extraordinary soul that has a humility and an integrity that comes from a deep love and respect. A love for the wild, life giving force of the ocean in all its moods and colours. A respect for its awesome power and unpredictability.

Mickey had done his countless hours swimming, paddling, surfing in waters all around the world. He’d also built unshakeable bonds with people from all walks. Sharing tales, always open-minded, never other than ready to glimpse the magic around him. So his creative work was suffused with a quality and sincerity that just can’t be faked.

The Dark Side of the Lens, a film Mickey made to explain his work to his sister Cherry, received a rapturous response when he played it in his 2011 Do Lectures talk. It's the most beautiful, powerful and poignant 6 minutes of visual storytelling I’ve ever seen. It brought me and countless others to tears. Mickey’s response to the raucous applause and cheering? He giggled. He grinned and giggled and hung his head and humbly said ‘thanks guys, thanks a lot.’

Mickey summed up his life’s philosophy for the Do Lectures audience. Arm yourself with a grin, embrace being out of control and let your weirdness flow free. Trust in the things you love, get primal with nature and take time to experiment and learn new things. Trust your instincts and run with them always. Use your fears and failures as fuel for the onward journey.

Mickey finished with an exhortation. Do what you love for a living he said, but be wise – don’t let the pursuit of money kill your enthusiasm for what you love.

In the Dark Side of the Lens Mickey explains his motivation for living for the ebb and flow of the sea. Dedicated to his now late sister, the film is bathed in a mournful quality. In it Mickey makes a confession. “If I only scrape a living, at least it's a living worth scraping. If there’s no future in it, this is a present worth remembering.” Mickey Smith will not go to his grave wondering what could have been.

Mickey Smith changed everything for me. His talk shone a bright light on the visceral power of humility and the need for authenticity. His philosophy is one I shared with my kids immediately afterwards. Mickey Smith is everything I hoped the Do Lectures could be. Mickey Smith is a king of life. I celebrate you Mickey Smith, Lord of the Waves.

Lessons from an old school Italian restaurant No. 9

Sometimes we just need to take our time.

I’ve mentioned before how my old man was forever telling me to slow down. I’ve been thinking recently how his recommendation to do so is more appropriate than ever.

We need more friction.

Everything is happening so fast, and so often without any foresight, it really feels like we could do with a little bit more friction.

Back in the day, when pretty much everything we made was analogue, things were naturally constrained by their material properties, their availability and the speed with which they could be made.

In the making we got to see how they worked, and how we might accommodate them and how they might irritate us, or cause problems. We had time to change stuff before it got out of hand. In the digital realm we’re losing that.

All that make stuff and ship stuff and break things that has been the mantra from the valley of silicon, seemingly forever, is I think, part of the reason we are in a bit of a fix.

There’s no friction anymore. It’s all a bit too easy.

My old man gave me and my old pal Jeremy Smith a perfect lesson in the benefit of friction when we were teenagers. With chips.

He’d bought some fillet steak home from the restaurant on Friday night and Jez and I were starving after a Saturday morning game of golf. Dad offered us medium rare with hand cut chips and a side of mushrooms. We were delighted.

Until he told us it would take a couple of hours.

Huh?

The potatoes need to be peeled, rinsed and cut he said, then parboiled, then drained and left in the fridge to cool for an hour. Then they need to be fried, then drained again, then set aside to cool. For about 20 minutes. Then the steak can go on he told us, the mushrooms can be sauted in butter, and the chips can go in for a second fry. Gently for another 10 minutes or so. Then the steak can rest. And then I’ll plate it up and you can have it.

And so we waited and we waited and we waited. Impatience and an empty belly are never a good combo. But we waited.

When we sat down to eat I understood. The steak was tremendous, that was expected. The mushrooms were fine. But the chips, well the chips were from another dimension altogether. They really were sublime. Crispy as a crisp on the outside and as melt in the mouth as an ice-cream on the inside. As close to a perfect thing as I’ve ever eaten. To this day.

Jeremy and I have been mates for close to 50 years. The chips come up every now and again. And he’ll tell you too. They were as close to perfect as you’ll ever taste. Thanks to friction.

Making is meaning

Matt Watkinson got me thinking hard a few Fridays ago. He frequently does, he’s absolutely one of the smartest, funniest, most thought provoking people I know. He has this knack of saying things which work away at your brain like a Beatles lyric. You just can’t get them out of your head. I’ve become convinced that this is a reliable heuristic that you’ve heard something deeply insightful. I’ve christened it the Watkinson Razor:

“When you hear something on a Friday and it’s still tearing around your frontal cortex and putting a smile on your face on Sunday, you can be sure it’s a deep insight.”

We were talking about how the Linkedin algo is currently dreadful in getting the stuff we actually want to see in front of us. Matt then made a great point about meaning - so many people seem to be looking for it in their work at the very same time that the world of work seems to be lacking in it more so than ever. He wondered whether that lack drove them to Linkedin for some connection. It seems likely to be the case to me, notwithstanding how many seem to be there purely with the goal of selling their unique, magic solution that solves for that lack. (Weirdly there seems to be a correlation with how magic the stated sauce is and how glitzy the accompanying Canva carousel looks).

Anyway, what Matt said that really got me thinking was that he doubted that a carpenter had a problem working out what the meaning was in his work. Or a plumber. I mean it’s difficult to argue against the point that the meaning is intrinsically in the making that they do. There is a tangible outcome, every time. And Matt’s very well qualified on this - he’s currently re-building an Airstream bolt by bolt, one CAD designed, 3-D printed part at a time. And only this week he’s been in the workshop manufacturing egg blowing equipment for his own Easter Faberge offering.

Now I’m not about to suggest that everyone working in an office re-trains in construction although God knows it would be a useful thing, and it’s high time we start celebrating and elevating the status of productive physical work. But what I think we have lost in all the soul searching about meaning and purpose, is the recognition that we won’t find it by shackling our identities to the pursuit of more status, more wealth, more power, or more thumbs up emojis. Either in the workplace or in the digital social realm.

Maybe our meaning is always tied to our making. Whether it be roof trusses, water systems, Airstream re-builds, music, or poetry. Or, paradoxically, things that we can't physically hold like relationships, connection and belonging.

Maybe if we think more about building useful things rather than vacuous things, we won’t need to keep talking about the search for meaning. It will just become obvious that we are living lives of meaning and the upside is we won’t need grifters on social media selling us the answers with a 7-point plan that we can master in 2 weeks if we just type “I’m in” in the comments box.

I keep going on about curiosity being the gateway drug to creativity, because I believe in the powerful nourishment that re-connecting to our deeply innate creativity provides. And maybe here’s the thing – fostering that re-connection to our curiosity, imagination, and creativity, will lead us to making bold, valuable, meaningful decisions. Joyful, inspirational decisions in the teeth of all the drama and volatility.

I asked my friend Adrian what he thought about it all. He’s a trained cabinet maker and joiner, and he runs construction crews making ultra high-end residential property. He’s also the most gifted carver and birch-bark weaver you’ll ever meet. This is what he said:

“I’d say my happiness quotient is definitely linked to the immediacy of my craft. Cut it, nail it, we have a roof over our heads. However the rise of the machine has dumbed down the craft. It’s all about tools and fixings. The maker/builder doesn’t need to learn anything new - just buy a new tool and find the right fixings. The skill is in knowing how to do just enough. That takes a constant will to do new things and then do them over and over again. Curiosity definitely feeds that will.”

Beautiful - there we are again - that recurring reminder that curiosity is the ultimate super-power.

The Linkedin Files

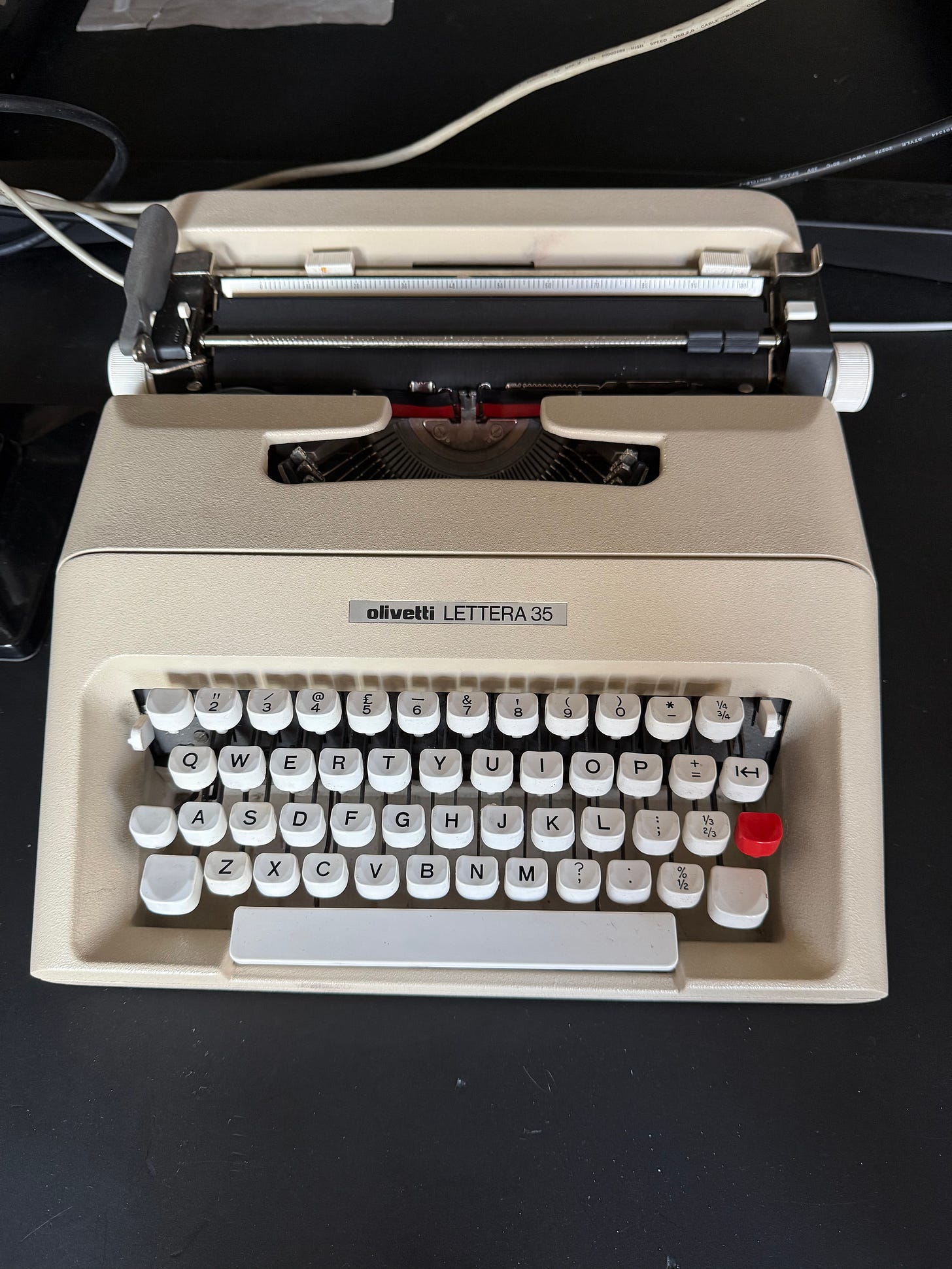

I’ve also got a bit fed up with all the AI LLM generated posts and comments on Linkedin. I’ve started a little analogue series on my Olivetti.

It fascinates me that these seem to have stimulated a warm response. I’m having some delightful interactions which suggests that plenty of us want more tactile, authentic and human connection than we’ve been getting. The lovely and always interesting Jonathan Trimble who writes a must-read weekly newsletter, sent me a lovely message which I think illustrates this well:

Tectonic

We’re in a world getting rapidly saturated with generative AI. We’ve already got zero cost LLM’s writing effective code and drafting so called thought leadership pieces (does that phrase make your teeth grind as much as it does mine?). We’re seeing pattern recognition machine models churning out design drafts of all shapes and sizes. In all the mayhem business leaders need to be asking at least one critical question: “What uniquely human qualities will drive success when AI can replicate so many patterns?” The answer lies in two timeless human traits: curiosity and imagination. These traits, these drives, form the core of the human edge, and they provide purpose and vision that no algorithm can give birth to. As the World Economic Forum’s latest Future of Jobs report suggests, “the future of work belongs to the curious and creative.”

Curiosity and imagination are closely linked, but they are not the same. Each represents a different cognitive drive, and together they form a powerful feedback loop. They feed and nourish each other. Simply put, curiosity is about exploration, while imagination is about creation. More of one, more of the other in a lovely self perpetuating loop.

I’m really interested in what happens when we effectively synthesise the two and use good taste and sharp judgement to reveal novel possibilities, and solve intractable problems more quickly and more effectively. I’ve seen it have extraordinary results. It’s what I call applied curiosity and it’s the foundational principle for the new strategy meets design studio that is Tectonic. Tectonic is borne out of a strongly held belief that it’s time to move from ROI - return on investment, to ROI return on imagination; and from ROCE - return on capital employed to ROCE - return on curiosity employed. We’re all here to generate positive impact, not just in business outcomes, but in societal outcomes, and we’ll do it much more effectively if we start to be genuinely brave.

Where the two long established business measures still matter, they matter less than the new ones. Without curiosity and imagination there will be no return on investment and no return on capital employed. This is not like the old days. There are hidden, and increasingly powerful shifts occurring all the time, and we’re starting to see the fissures. The advent of powerful generative AI has dramatically changed what technology can do – but it has also thrown into sharp relief what only humans can do. Today’s AI systems excel at processing vast quantities of data at unimaginable speeds, in recognising patterns, and even in producing what look to be genuinely creative outputs by recombining what they’ve learned from their training data. But what they lack, and what they will always lack, is the intrinsic curiosity to define novel problems, to connect the unconnected, and to fire an imagination which can conceive of something radical and original. In a post-generative AI world, human curiosity and imagination stand out as defining superpowers precisely because AI cannot and will not fully replicate them.

The Tectonic offer brings applied curiosity to the boardroom not to add more complexity (we don’t like that) but to cut through it - to generate simplicity beyond complexity. It brings the benefits of cross-domain intelligence, imaginative framing, and strategic insight to the highest levels of business decision-making.

When all of our competitors have the same AI tools as we do, our critical edge can only come from how well we think, how deeply we see, and how boldly we imagine — not from how fast we automate. However the AI revolution plays out, for now everyone is competing on the same ideas and fighting for the same customers, using the same tools. That’s the route to becoming rapidly indistinguishable and a short stop from someone more imaginative eating our market. Many of us are already experiencing business models under severe strain. If you’re not sure where to look next I may be able to help.

Finds from this month’s excavations

Music: More Crazy. This is what happens when great artists collide - Cee-Lo and Daryl Hall. Yup. You can’t go for that? Well how about this?

Hellraisers: Two of the finest hellraisers of all time. Good actors too. And they love their rugby.

Silly aphorisms: I know I’m a grumpy old bas**ard but help me out. I keep reading these silly little aphorisms in newsletters and I have no idea what they actually mean. Please email me help:

“Rejection isn’t a verdict; it’s data. Use it.”

“Everyone dreams big until they see the price tag.”

Specialisation: Nah. I’m with the late American naval officer, aeronautical engineer and sci-fi author Robert Heinlein:

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyse a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.”

Science: Neil deGrasse Tyson on why Isaac Newton is the greatest scientific mind in history.

Craftsmanship: When exquisite craftsmanship and wonderful storytelling meet. Made in Britain.

Vinyl: My big Easter listen was Spirit of Eden by Talk Talk - an absolutely monumental album from 1988 which provided the soundtrack to my in-between year after Catholic school pre- University. There’s nothing Catholic about the freedom and experimentation in this wonderfully expansive creation. It’s staggering in its depth and scope. Radiohead before Radiohead. And more. Mark Hollis was so criminally under-rated as a songwriter at the time. Guy Garvey did a wonderful evocation of the album years ago but the BBC link seems to have expired. Here’s another on the band.

RIP: Pope Francis